Digital communities are collections of individual entities that are connected together. They can be modeled as graphs, with the individuals being nodes and their relationships being edges.

Traditionally, identity models have focused on the nodes, but in Musings of a Trust Architect: Edge Identifiers & Cliques, I suggested that both private keys and public-key identifiers could be based on the relational edges, and that when you combined a complete set of edges you could create a cryptographic clique, where the group was seen as an entity of its own, with the identities of any participants hidden through the use of a Schnorr-based signature.

My first look at cliques focused on the technical definition, which requires that cliques be “closed”, meaning that there’s a relationship between every pair in the group and that those pairwise edges form the clique identity among them.

However, creating closed graphs becomes increasingly difficult as the graph size grows. There are some alternatives which I discuss here: open cliques and fuzzy cliques. The entities forming a clique also don’t have to be people, as I discuss in cliques of devices.

Open Cliques

Cryptographic cliques don’t have to be fully closed. Open cliques are also possible. (In graph theory these technically are not called “cliques”, but I’m going to continue to use the term for cryptographic identifiers that are based on edges.)

While the concept of a fully connected clique provides clear value in graph theory, such structures can become computationally intensive, especially as the group size increases. Open cryptographic cliques, which are not completely interconnected, may then be used instead.

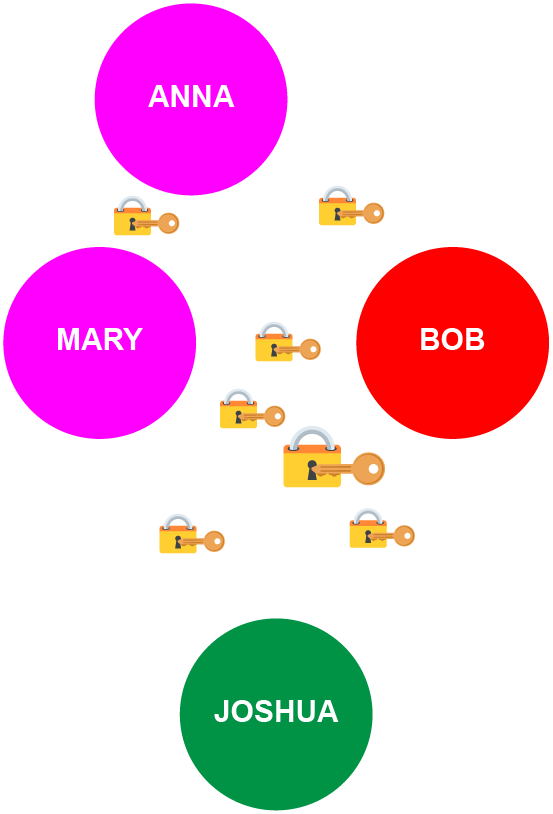

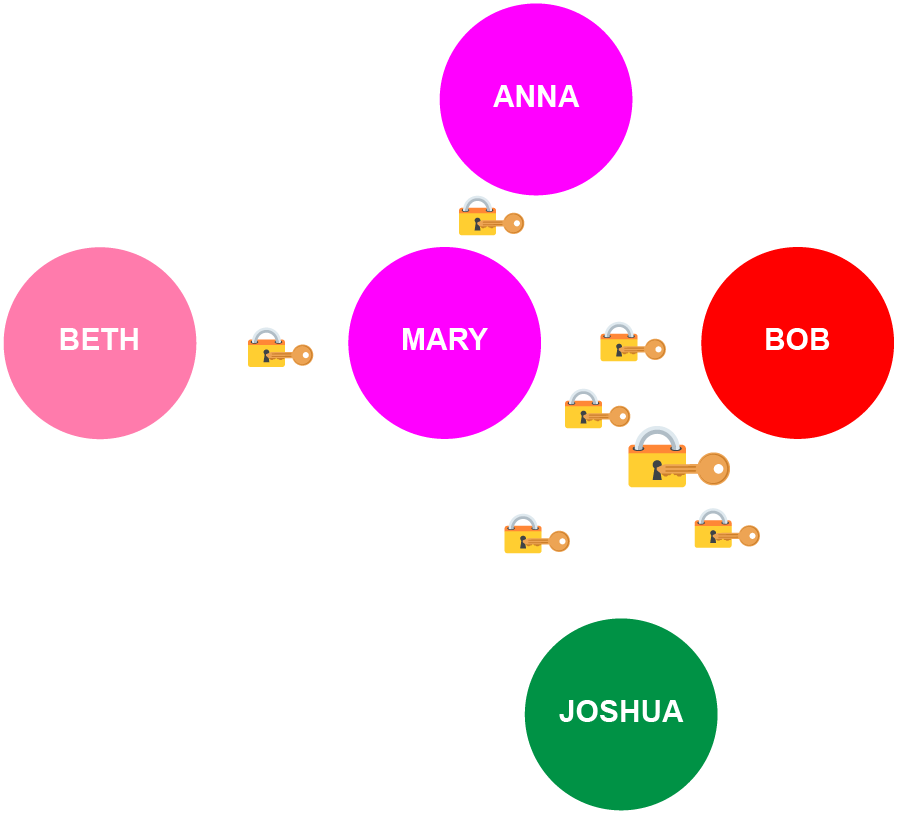

Open cliques support different sorts of modeling, for groups where not everyone is connected and where the relationships are fluid. They also allow for easier growth: a clique can organically add a new member when a single participant creates a relationship with them, without the need to define the new member’s relationship to everyone in the clique (especially as most of those relationships would not exist).

For example, Bob might not actually have a close or independent relationship with his mother-in-law, Anna, while Mary’s best friend from college, Beth, might join the clique when she stays with the family, despite the fact that she only has a real relationship with Mary. (However, more relationships, and thus edges, might develop over time!)

While open cliques may lack the complete interconnectedness of their closed counterparts, they offer a realistic representation of the evolving nature of dynamic social relationships. One of the main questions regarding them is when and how to recognize new edges as an open clique evolves, and thus when and how to rotate the clique’s overall keys.

Fuzzy Cliques

As discussed in the appendix to this article, there are currently two major Schnorr-based MPC signature systems that could be used as the foundation of cliques: FROST and MuSig2. Each comes with its own advantages and limitations, but one of the advantages of using FROST is that it allows for the creation of fuzzy cliques, thanks to its ability to create threshold signatures (with m of n agreement required to sign where m≤n).

This allows group decisions or representations to be based on a subset (threshold) of members rather than requiring unanimity, as would be required when using MuSig2 in its native form. Using thresholds to define group interactions adds a degree of “fuzziness” or flexibility to the representation of those groups and their actions, at the price of higher latency and the fact that the theoretical implications are not as well studied.

There’s one other catch: fuzzy cliques are the one situation where the Relationship Signature Paradigm can’t be used. Though we still create the relational edges, to allow any pair of participants in the clique to make joint decisions, the clique keys are created by the individual participants, not the edges, ensuring that we have thresholds of participants making decisions, not thresholds of edges (which would quickly become confusing!).

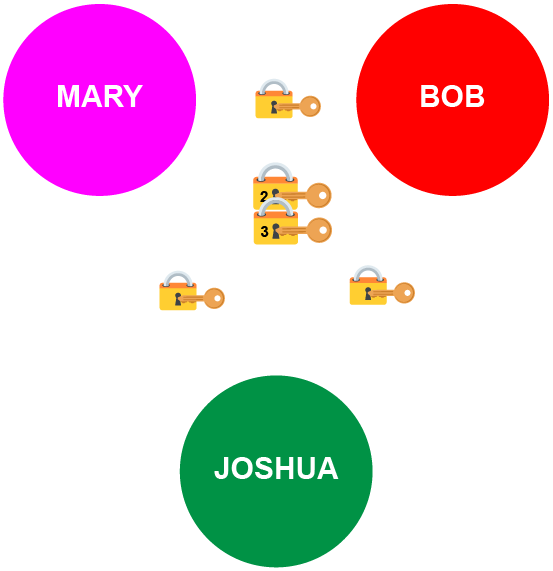

Even for a triadic clique, the privacy implications of using a threshold key to represent the clique are notable.

Imagine that the participants generated two FROST keys for the triadic clique, one that had a 2-of-3 threshold and one that had a 3-of-3 threshold. If every one agreed, they could all sign with their share fragments of the 3-of-3 private key, and anyone could compare it to the 3-of-3 public key and know that the group was in perfect consensus.

But what if you only required the consensus of two members of the group? After all, Joshua probably won’t be making a lot of decisions for a while. Theoretically, you could just sign with one of your relational edge keys, such as the Mary-Bob relational edge key. That demonstrates the consensus of two members of the clique and supports accountability: you know which two participants signed.

But, if you instead sign with the 2-of-3 threshold key for the clique you get to take advantage of the aggregatability that’s baked into Schnorr. With it, no one knows which two people signed (or indeed, if two or three people signed). They just know that at least the threshold of people within the group signed. It’s a powerful privacy enhancement that really shows off the power of fuzzy cliques.

Fuzzy cliques allow for real-world decision-making dynamics, where different sorts of decisions might require a single person’s agreement, a majority’s agreement, a super-majority’s agreement, and everyone’s agreement. This creates a model for fully decentralized decision-making that’s resilient and fault tolerant, all while supporting both individual privacy and group accountability (which still allowing for individual accountability using relational edges).

Cliques of Devices

Thus far, I’ve largely presumed that relational edges and cryptographic cliques are created by people. But, that doesn’t have to be the case: independent nodes in a graph can be entities of any type, including devices.

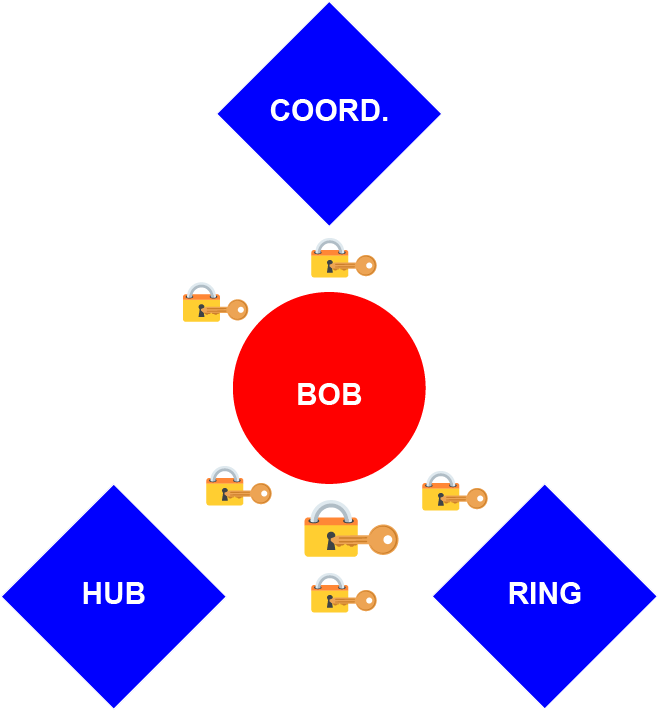

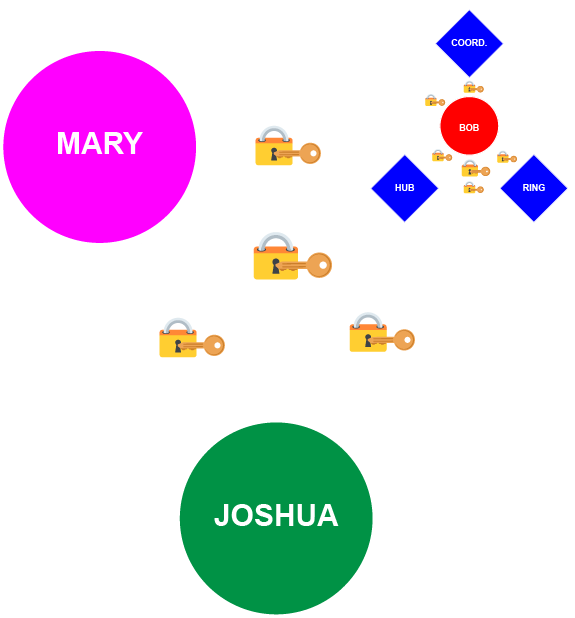

In my first article, I touched upon the idea that a clique could define not just a group, but also a singular person’s identity. This could be done using devices. Imagine that a person has a few devices that together form the basis of his digital identity: a hub of information that contains his credentials; a biometric ring that verifies his physical identity, primarily to unlock that hub; and a coordinator that allows a clique-identity to communication with the network. The following diagram shows how our old friend Bob could be defined as an open clique including devices:

Using the clique-of-cliques model, this then might be the identity that’s linked in with Mary and Joshua to form their triadic nuclear-family clique:

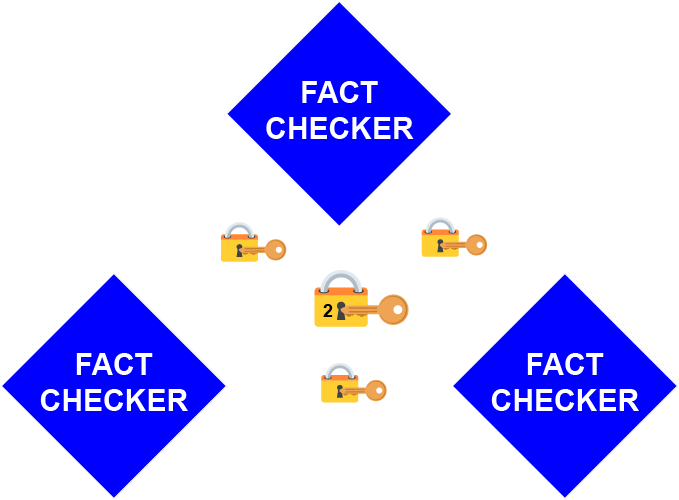

Though these examples suggest a clique where devices and real people are mixed together, that’s not the only option. Another example might be a fuzzy clique made up of three automated factcheckers, which are all devices. Together, any two can issue a finding of “TRUE” or “FALSE”:

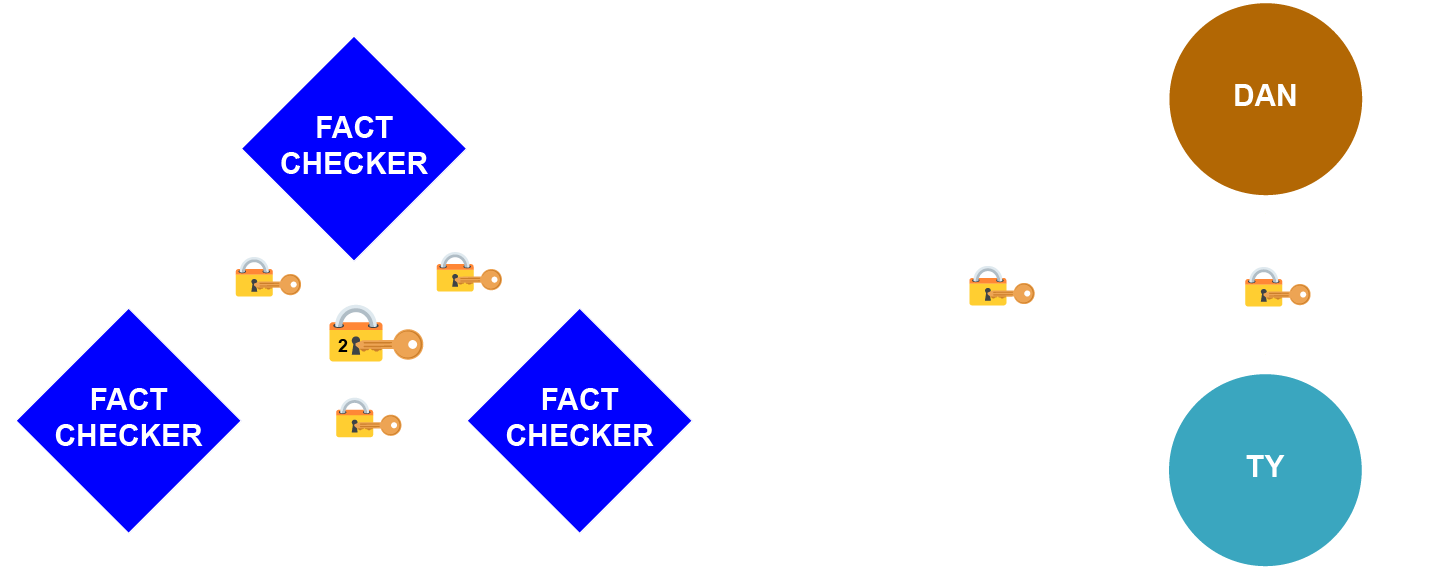

Again using the clique-of-cliques model, these fact checkers could then interact with other identities, such as Dan and Ty, who write together.

The Fact Checkers interact with the authors’ edge relationship (known by their joint pseudonym, “James”), to sign off on the validity of their work. Thanks to the aggregatability of Schnorr signatures, no one knows (or cares) that the Fact Checkers are three devices or the authors are two people!

Conclusion

Cliques offer a powerful new model for identity control (and more generally, for control of many sorts of digital assets). But, using closed cliques has drawbacks.

Two other models offer different utility:

- Open Cliques allow for the modeling of more realistic social situations while simultaneously reducing compuational costs, but create new questions for theoretical understanding and in figuring how to maintain public and private keys for the clique.

- Fuzzy Cliques open up the possibilities for authorizations, agreements, and other decisions to be made by portions of a group rather than the group as whole, but they depend on either FROST or some other (theoretical) threshold signature system, and they disallow the creation of a clique using relational edges.

In addition, cliques don’t have to be made up only of people:

- Cliques of Devices show how cliques could also include AIs, oracles, fact checkers, hardware wallets, biometric rings, and other computerized programs, and that they could interact either as parts of cliques or as separate entities!

These possibilities are just the beginning. I think that edge identifiers and cliques could be a powerful new tool for expanding the design of identies online.

How could you use them? How would you expand them? What would you like to see next?

Appendix: FROST & MuSig

There are currently two major Schnorr-based signature systems, FROST and MuSig2, both of which support Multi-Party Computation (MPC) signing.

FROST is a Schnorr-based multisig system that originated in a 2020 paper. As of 2024, it’s just coming into wide use thanks to projects such as ZF FROST and wallets such as Stack Wallet.

- 🟢 Possible efficiency improvements for larger cliques.

- 🟢 Supports thresholds (m of n).

- 🟢 Privacy for thresholds.

- 🛑 Limited accountability for thresholds.

- 🛑 Can’t build clique from edges if using thresholds.

- 🛑 More rounds for signing.

- 🟨 Allows Distributed Key Generation or Trusted Dealer Generation.

MuSig2 is a Schnorr-based multisig system that dates back to 2020 (when MuSig2 was introduced) and before that 2018 (when MuSig1 was introduced). It’s been well-studied and is detailed in BIP 328, BIP 390, and BIP 373, providing strong integration with Bitcoin, especially since its recent merge into libsecp256k1.

- 🛑 No thresholds (n of n).

- 🟨 But can mimic thresholds with Taproot trees

- 🟢 Full accountability for signatures.

- 🟢 Fewer rounds for signing.

- 🟢 Can always build clique from edges.

Two of the features of Schnorr-based signature systems that best support edge identifiers and cryptographic cliques are aggregation and MPC.

- Aggregation. Schnorr signatures are aggregatable. They’re mathematically added together, producing a final multisig that’s the same size as an individual signature would be. As a result, signatures are indistiguishable: you don’t know how many people signed or who signed, simply that a signature is valid (or not).

- MPC. Multi Party Computation means that each participant has a secret (here, a key share), which they can use together without revealing that secret. It’s what allows individuals to jointly create an edge-identifier key and then for edges to jointly create a clique key.

For more on Schnorr, see my Layperson’s Intro to Schnorr.